The most heated topic in NatsTown right now is batting order. However, since Joe at The Nats Blog, Court and Frank at Nats101 and the Huzz have all covered this topic extensively; I’ll write about the second most heated topic in NatsTown: sac bunting.

Let’s get two things out of the way before we begin: one, we’ll only discuss non-pitcher sacrifices, since that makes things simpler, and two, spoiler alert, there are specific situations where a sac bunt attempt is beneficial. Okay, let’s get started.

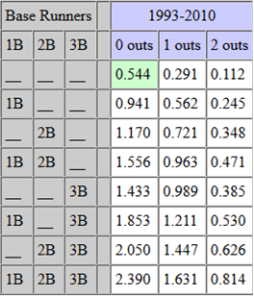

To start with here is a run environment table from 1993-2010 courtesy of Tom Tango. Using real-life baseball game data we can determine the average number of runs a team can expect to score through the end of an inning based on the current base-out state. This table then neatly orders these results into an easy to read format. On the left is the runners on base and where they are, and on top is the number of outs in the inning. For our purposes though, we’re only concerned with those states that occur when a batter would be asked to sacrifice and the resulting state if the sacrifice was successful. So let’s trim that table down to just these states.

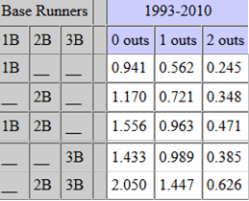

Using real-life baseball game data we can determine the average number of runs a team can expect to score through the end of an inning based on the current base-out state. This table then neatly orders these results into an easy to read format. On the left is the runners on base and where they are, and on top is the number of outs in the inning. For our purposes though, we’re only concerned with those states that occur when a batter would be asked to sacrifice and the resulting state if the sacrifice was successful. So let’s trim that table down to just these states. The idea is that when we transition from what state to another we’d like the average number of runs we’re expected to score to increase. Looking at the traditional sac bunting situations we can see this isn’t the case. The cost of going from zero to one outs, or even worse one to two outs, trumps advancing the base runners by one base.

The idea is that when we transition from what state to another we’d like the average number of runs we’re expected to score to increase. Looking at the traditional sac bunting situations we can see this isn’t the case. The cost of going from zero to one outs, or even worse one to two outs, trumps advancing the base runners by one base.

So that’s it then, right? Never sacrifice bunt? No, I just told you that there are specific situations where a sac bunt attempt is beneficial, please try to keep up.

We have only considered situations where the bunt works as planned 100% of the time. Obviously, this doesn’t happen in the real world. What if there are times where the other events add up to enough of a positive affect it outweighs the normal run expectancy?

In the literally titled book The Book by the same Tom Tango, Mitchell Lichtman and Andy Dolphin, there is a chapter devoted to sacrifice bunting. In it they cover what we can expect to happen when the average hitter attempts a sac bunt based on real game data. From this they drew some conclusions, cleverly packaged as “The Book says,” as to when it would be beneficial to just attempt a sac bunt. To save you the trouble I’ve pulled some of the more relevant ones. All of these points assume there are no outs, as we saw above the run environment is so low with two outs that there is nearly no benefit from a sac bunt attempt with one out.

“In an average run environment, and not considering the bunting proficiency or speed of the batter, or the speed of the runner on first, if the batter has an expected wOBA of less than .300, 44 points less than the league average, he can attempt a sacrifice bunt, even if the defense is expecting one.”

Unsurprisingly, with a weak hitter, the unintentional benefits of an attempted sac bunt can give us a higher run expectancy than if that hitter just attempted to swing away.

“All other things being equal, sacrifice more often with a low-walk, low-OBP hitter on deck.”

With the runner on second with one out the value of most events is the same as it would be with the runner on first with no outs, except for the walk. Walking puts the force play back on without advancing the runner again. So, in comparison to other sac bunt attempts, a sac bunt attempt is much more beneficial when the next hitter is one that does not walk as often. This is not to say that you should always attempt to sac bunt in front of a weaker walking hitter.

“In an average run environment, almost any batter can bunt as long as he is a good bunter, or a fast runner, preferably both. A poor or slow bunter should rarely be allowed to sacrifice.”

Again this shouldn’t come as a surprise that a good bunter or fast runner can get more of those unintentional benefits of a sac bunt attempt. What might be surprising is that the benefits are so great, it can actually outweigh swinging away.

“With a runner on first or first and second, and no outs, the batter’s GDP rate (adjusted for the pitcher) should be considered in deciding whether to bunt or not.”

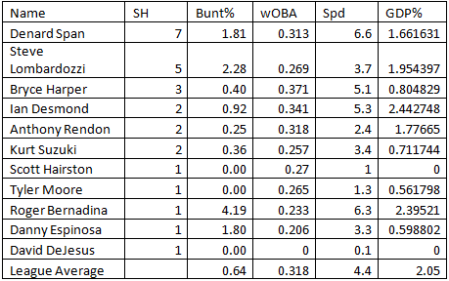

So what does this mean for the Nationals? To begin with here’s a list of the players who had a sacrifice hit in 2013, along with their non-sacrifice bunt rate, wOBA, speed rating and ground ball into double play rate along with the league average. We include non-sacrifice bunt rate based on the idea that a player who attempts non-sacrifice bunts often is a good bunter.

For the most part the Nationals did a good job with who they had sacrifice bunt. Now this information is a bit incomplete since it only shows those who were successful, but it should still give us a good idea as to who was called upon to attempt a sac bunt. Nearly every player has a wOBA below league average. The top two, Span and Lombardozzi, have well above average bunt rates, indicating that they are good bunters. Span’s speed score is also well above average, while Lombardozzi has a fairly high double play rate. These factors would indicate that both are good candidates to be attempting sac bunts.

Among these players two names definitely stick out: Bryce Harper and Ian Desmond. Despite his high wOBA Desmond’s high bunt rate, good speed and above average double play rate likely could justify the occasional bunt attempt. Harper on the other hand, does not attempt bunts often, is a well above-average hitter and grounds into double plays at a well below average rate. He should not be attempting sacrifice bunts.

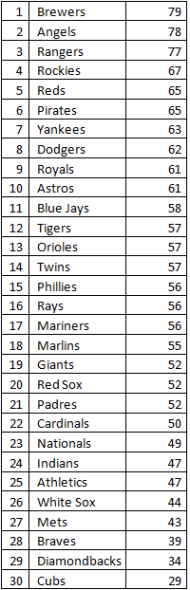

One thing the astute reader may notice is how few sacrifice bunts the team had as a whole, just 26. Here’s the total number of sac bunts by each team over the last two seasons.

Under Davey Johnson the Nationals had the 23rd-most sacrifice bunts, below the Major League average of 55.6. New Nats manager Matt Williams’ old team, the Diamondbacks, executed even less, finishing 29th, well below league average.

Under Davey Johnson the Nationals had the 23rd-most sacrifice bunts, below the Major League average of 55.6. New Nats manager Matt Williams’ old team, the Diamondbacks, executed even less, finishing 29th, well below league average.

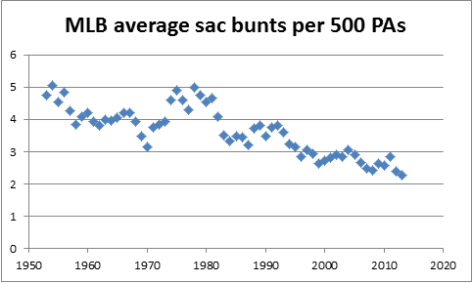

Not only are the Nationals on the low-end of the league, the league itself is executing less sacrifice bunts than ever. Here’s a scatterplot of the average number of sacrifice bunts per 500 plate appearances over the last 60 years.

Outside of a brief renaissance in the 70’s the sac bunt has been on a downward trend and in 2013 the league average was just 2.28 sacrifice bunts per 500 plate appearances. For those who hate the sac bunt their time is now. Outside of a few exceptions teams don’t employ the sac bunt anymore.

Outside of a brief renaissance in the 70’s the sac bunt has been on a downward trend and in 2013 the league average was just 2.28 sacrifice bunts per 500 plate appearances. For those who hate the sac bunt their time is now. Outside of a few exceptions teams don’t employ the sac bunt anymore.

So, while the strategy of trading an out for a base is a terrible one, there are certainly some situations where attempting one can actually produce some unintentional positive benefits. And in any case, teams, especially the Nationals, barely sac bunt to begin with, so it’s likely not worth getting too riled up over on the rare occasion that a player squares around. Unless it’s with one out, then kill the manager.

Great Post James. I may follow in your footsteps a few months from now on this topic. That said, a “Kill the Sac Bunt” shirt may be too cool to pass up even with your very well reasoned article 🙂

LikeLike